- Home

- Jane Borodale

The Book of Fires Page 2

The Book of Fires Read online

Page 2

It was September, the busiest time of the year.

“Agnes!” she is shouting. I forget myself, am nearly spilling the blood out onto the stones in the yard. I level the pot. There is so much pig’s blood, perhaps eight full pints of it. There are red splashes all over the ground, and my feet ache with the cold.

“What is the matter with you, dreamy girl?” my mother scolds. Her breath is white all round her in the cold air, so that I can hardly see her mouth.

My uncle slits and empties the pig in a rush of dark bowels. It is washed. We are all there watching when he pulls out the heart. It is marbled with a fan of yellow fat, like veins over a leaf.

Then he hangs the pig from her back legs, big in the outhouse, and two days pass for the flesh to become firm.

Its presence is everywhere; a twelve-score weight pulling at the hooks between the tendon and the ankle. The head hangs straight under the spine although the throat is cut, and pink fluid runs down the snout and drips into a pot upon the ground.

When I go to the outhouse to fetch soap for the laundry, William is there scolding the cats away from the bucket of soft parts that we have not yet eaten. He picks up a twig and pokes in among the wetness.

“What is that?” he asks. I look, and tell him that it is the stomach.

“The slippery stomach, the slippery stomach, shall we tickle it, shall we?” he says, and shrieks in horror at his own joke and runs away.

I take my turn at the loom.

It is a quietly complicated object, causing nothing but a runnel of thoughts to slide evenly through my mind as my hands follow their task at the shuttle and threads, in the same way as a horse will step along a familiar route without heed or guidance. When my hands are engaged in this way, the thoughts of trouble that rankle inside do not take me over. It is when the racket of the loom ceases abruptly that the twisting panic returns and plunges a kind of darkness through my head, as though a sharp wind had gone through a house snuffing out candles and leaving space for fear. I arrive at that point early in the day when I have sat out one hour at the loom.

“Agnes!” my mother shouts suddenly into the back chamber, making me jump. “We are short of a skillet! ”

So I leave the house to get the pot, my ears buzzing with the silence of my stopped work, and head out on the lane as I am bidden. My mother’s voice, muttering instructions to Lil as they prepare the stew, dwindles and then vanishes as I walk. The sun is out, and sparrows flit and whirr between the hedges.

Mrs. Mellin is our closest neighbor and her house lies in the opposite direction to the village, along the muddy white road that leads to the chalk pit. She lives declining and alone; her son was taken away by the press-gang in a port on the coast three years ago, and was said to have died of drink or bullying. Her husband has been dead for as long as any of us can remember. He died on a Sunday; Mother said he was a thoughtless man who had left his wife little but bad habits.

It is a pleasant day, and for all our troubles perhaps the winter may not be so bad. There is a blue sky above the top of the ridge of the Downs, and sunshine is shivering patches of brightness through the trees by the side of the road as I walk. But the sun is getting old now for the year. Sitting lower in the sky each day, it hardly warms the ground at all, and my feet walk along the lane in shadow.

Her cottage sits tightly into the base of the scarp, the steep coppice threatening to swallow it. I call loudly as I approach, and hear how her chickens make a fuss and clamor at the side of the house. The door at the front is shut and I lift the latch and push it open, bending straight into the coldness of the parlor. A brown cat rushes outside.

“Hello!” I call. “Good day, Mrs. Mellin!”

Mrs. Mellin is deaf, and she doesn’t answer my greeting as I clatter about, choosing a skillet. The pots are loud and hollow on the worn brick floor as I stack them into their habitual places behind the dirty cloth stretched under the shelf. I go into the kitchen, where she is always. She has her back to me, sitting in front of a stone-cold grate. “Oh!” I say in concern. “Why is your fire out, Mrs. Mellin?”

And I am shocked. Mrs. Mellin is dead in her chair. Her purple tongue is sticking out and her eyes are rolled back in her head. Her arm lolls down over the edge of the chair. On the floor, as if it has rolled away from her, is a small china jar, the jar that usually sits on the left of her mantelpiece. The lid is further away, almost out of sight, right under her chair. My mouth is dry.

“Oh, Mrs. Mellin.” I am afraid and sorry. My heart beats very fast. I talk to her as if she were asleep as I prop her head and push her eyelids closed. I expect her body to be stiff but she is soft and limp. I don’t look at her tongue and I hear myself talking giddily to her in a way that I don’t recognize. She doesn’t need me to be foolish, but I talk and talk. I pick up her fingers between my own and fold them into a sensible arrangement in her lap. She looks more ordinary now, although I still don’t look at her tongue. Her hands are neither cold nor warm; they are the same temperature as the wooden chair that she is sitting on. Mine are still warm after walking fast up the lane in the sunshine; I see I still have black blood under my fingernails. I sit down on the settle at the other side of the hearth to gather my breath and ask myself to whom I should run and ask for help. It is a long way to the rectory. I stand up again. My mother will be working without me, thin and tired after the long day boiling pudding and preparing to salt the new pork flesh in the big trough. When it is done we will wash off the salt and hang the sides from the iron hooks at the back of the hearth in the smoke. I should go home again. I am ashamed to think of eating, but a sudden thought of the taste of meat makes my mouth flood with water.

I do not know how much time has passed. I lean forward. Perhaps I have made a mistake and Mrs. Mellin is just asleep or ill. Perhaps she needs help. She is not much liked. I lift her eyelid back up, gingerly. Her eye is yellowish blank and I notice that there is an odd smell about her, as though she were already changing into another substance. No, I have been around dead things enough now to know that Mrs. Mellin has been gone for some days. I stand back; I must send a child to tell the rector she is deceased. He will come and he will say some words and let her fingers touch the cover of his Bible and then they will bury her and that will be that. I bend down to pick up the fallen jar beside her chair and glance inside.

And there are the bright coins.

They spill out and roll and clatter on the floor in my surprise. They gleam and flash astonishingly as I bend again to pick each one up and turn it over in my fingers. I count a guinea; a half-guinea; one, two, three, four, five crowns and a handful of foreign gold, perhaps from Spain. The burnish on them is high, as if she had spent time polishing each one. They are so bright: brighter than rosehips in a dark hedge, than birch leaves in October, than celandines or toadflax, than stones still wet from the riverbed, than yellow fungus in the coppice, than the yolk of a hen’s egg. They are like . . . fire. Like the sun.

And then the coins change as I am holding them and begin to show their value to me. My heart begins to beat so fast that I can hardly hear the plan taking shape inside my head.

2

The half-mile home along the lane seems a great distance. It is bright out here, and hurts my eyes, my crisp shadow bouncing along ahead of me between the bank and the hedgerow.

There are no flowers, save some tight, worn heads of black knap-weed, although matting caps of toadstools like soft flaking eggs are pushing through the moss and grasses. The ridge of the Downs is a great bulk above me, like the darkness of an animal waiting for the sun to set. At the bend by the place where the stream curls inward and almost touches the lane, flooding it over during wet times and washing the bones of the road smooth, I meet a traveling man. He comes along from Steyning way, with a tall pack on his back that makes him stoop sideways with the burden of it. The shadow he casts is stretched out and misshapen on the bank.

“Will not persist,” he says, implying the sunshine, halting for br

eath and glancing awkwardly up at the sky. He cocks his head backward as best he can, to the east beyond the line of beechwood on the hill. His voice is thin and weaselly.

“A great weight of fog rolling in off the sea is pressing in over the scarp, down there. No doubt we’ll be near to choking with it,” he adds with a gloomy relish, “before the night has encroached itself upon us.” He has a curious manner of speech; his eyes are very keen and they look me over, taking in my shape, my hands, the skillet. He blocks the way. I pull my shawl closer about me, and ask what it is that he has in his pack. It is bound up with strips of fabric, all grimy with dirt from the road.

“Sellings,” he replies inscrutably. “Buyings and sellings.” The man looks down at the road and passes me and rounds the bend, but the thought of him grows like a canker in my mind as I walk on. I see that my shadow is already fading in the road ahead of me, and that the man’s footprints are deep in the mud all the way back to the house. Clots of blackberries are finished and moldering in the hedgerow, and the undertow of a loamy smell of rot and fungus hangs in the air.

Inside the house I see that my mother has unstrung the pig, and struggled it onto the bench. It is heavy on its side, and judders with fat when William rocks the plank to show me. “Mother’s cross. She’s shouting,” he whispers at me plaintively. I touch his upturned face and wink at him to stay in the kitchen and guard the pig from dogs and rats. My mother is pouring the hot kettle over a board. She doesn’t look up from her cloud of steam.

“Did she spare the skillet then, nor mind us asking?” she says. A strong smell of scalding wood fills the room.

“Why did you not wait for the men to move the pig, Mother?” I say. I wish she would look at me. How I wish I could beg her to glance up now and notice me, to see how things are wrong. Standing there I count to four inside my head.

“Oh, I must get on, Agnes,” she says, slamming the kettle back on the black hook over the fire. The hook shakes with the weight. “The skillet!” She holds out her hand. “Your father’ll not be back before midday if I know him.” Her voice is flat and tense. “No, Hester!” she shouts abruptly. “Put that down! ” And I reach out hastily and take a bowl away from the baby before she breaks it on the floor.

My mother sits down then and rubs her sleeve over her forehead, and I see that her face is long and gray and tired, which makes the disquiet twist about inside me like a worm. How would she get by, were I not here to help her in the house? But of course from the back room the noise of Lil working the loom comes regularly hissing and clacking like a mechanical breath.

“Where is Father?” I ask.

“Where do you think, Ag?” she says shortly.

Hester begins to crawl to me, gurgling with effort, her baby’s gown dragging at her knees through the dirt as she crosses the floor that wants sweeping. I wait again for my mother to ask me why my errand took so long, but she does not, and so I blink and turn away. Perhaps the fire needs to be stoked; I bend over the hearth, pushing the logs closer together to coax at the heat. I wish that color wouldn’t rush so readily into my cheeks. I begin to talk up cheerfully about Mrs. Mellin’s skillet.

“She did mind, the old witch, but I promised her a bit of meat after the curing was done,” I explain lightly. It is my first lie of such proportions, and it comes away from my tongue with an ease that I don’t much like. The tended flames gather and spark brightly from the wood.

When my uncle arrives with his boots crunching on the path, and the butchering itself begins, I go straight to the trestle to cut up the onions, and turn my back. I find the smell of the pig is too strong this year for me to stomach. The blood is too red, the skin too much like my own. I have to swallow over and over to go on with the cooking.

My uncle is good with the butcher’s knife. Not like my father, who has not the patience. When I was smaller I liked to watch him cut up the carcass. There was a kind of miracle to the ease with which he separated the sides from each other, as though this were the way that nature had intended after all, it being so neat. I liked how the meat shrank away behind the cut of the knife as he worked, as if he had only to touch the meat in the right places to make it part of its own accord. Not the bones, though, all splintery rasping and sawing with blades to break them apart. Nor the fibrous caul that is beaded with fat around the stomach where the belly is flatter; he had to tug and rip at that to take it away to put into the larding pot. There should be six pints of lard to render and boil and strain from this pig, and some left to beat into flour to make flead cakes.

“Oh, the fat smells good!” William is excited and jumps about, holding the spoon. When he skims off the scum as it rises his little mouth is opened up with concentration.

The whole pig’s head boils whitely in a deep pot at the edge of the fire. I always set the pot so that the snout faces inward to the flames, as though it were warming itself and cannot see what we are doing to the rest of the body. I keep it covered to the ears so that it cannot even hear what we are saying, until it falls softly apart in its own juices. When it is done and taken away from the heat and cool enough to touch, William will sit and pick the head bone clean. He has a way with being careful, although he does not skin the tongue himself.

I am thinking, thinking.

At first in Mrs. Mellin’s kitchen the thoughts had flung themselves from side to side in my head, like water does in the pail on the walk from the well. I’d paced about. My heart had beat so fiercely that I was afraid for it and pressed my fingers at my chest bone. All the time the coins were winking brightly at me, a yellow pile upon the wooden table. I had hardly dared to touch the coins again, although my fingers left the place over my heart from time to time and hovered near.

Are they a sign from God? I’d thought.

Shall I leave them untouched? Are they a check upon my honesty? Are they a gift from Providence? Are they tainted by death? Do they belong to God now? How much is a burial? Is gold the Devil’s property? What is the punishment for stealing from a corpse?

The hens were fighting outside in her yard.

I’d scooped grain from a bushel sack and stepped outside. It was somehow surprising that the same sun was still shining. I took a breath. The leaves on the beech trees and the birch were vivid and they caught at the light, making many shades of yellow against the blue sky. Two finches swayed on thistle-heads, plucking out seeds. The air was fresh and clean, a cold, scouring kind of air, making the world seem washed and bright. It could be hard to conceal a secret in such an atmosphere of clarity, I’d reasoned.

I flung handfuls of grain and they drummed the ground firmly, as heavy rain does when it strikes baked earth at the start of a summer downpour. The hens strutted and flustered. It was extravagant to give good wheat to the birds, but Mrs. Mellin would not be needing flour where she had gone.

I almost laughed at how the world had changed so sharply.

The yellow coins had made my head feel light and free, quite a separate feeling from my bigger quandary.

Only six of Mrs. Mellin’s hens were left. A fox had taken the rest in October when the ground was hard with the second frost, creeping low out of the edge of the wood like a living shape of fear. The chickens that were spared the slaughter sat in the lower branches of the ash tree for two days until hunger drove them down again to scratch at the earth as if nothing had happened.

I brushed my palms together to get rid of the wheaty dust and the feel of Mrs. Mellin’s dead skin against my own. I took a breath. How cold and clear it was. Outside in the yard the world felt calm and ordinary. I counted some beats of my heart, eighteen, nineteen, thankful that no one could hear it.

And I realized that if I were gone from here, nothing would change. Any space I left in the world would fill in quickly, as earth closes in when you pull beets up from the ground.

I will take my disgrace elsewhere, I’d thought. I must run from here, until my shame is over or changed.

Quickly I’d gone inside and bound the top of th

e sack of grain closed to keep out rats. I took up most of the coins and gathered them flatly into a coarse piece of cloth. I put one to my lips as I did so; I could not help but touch my tongue to it, and bite. It was cold and hard. The metallic taste was almost like blood, and a ball of my white breath puffed out into the cold air of the room. I folded the cloth tightly and tucked it between my stays and my skin. When I breathed in, I could feel the lump of the coins pressing my rib cage. My ears strained for any sound of footsteps on the path, and I glanced again and again through the dirty glass of the window facing the lane. I replaced the china jar on the mantelshelf neatly with the chipped part facing the wall. Inside I’d left two pieces of Spanish gold to pay for the burial, this being only seemly, and knowing as I do how one should never cross the dead unduly.

“Mrs. Mellin.” I nodded to her body sitting there, and then left the cottage. Just in time, I had remembered the skillet.

How long ago that seems already, though it was only this morning.

“Two days per pound, salting,” my mother calculates, “which takes us to one month on Thursday next.” She eyes the powdering tub.

“I’ll do that, Mother,” I say. The cut meat is a bright, deep red in the flicker of firelight.

I feel dizzy. By a month on Thursday next, I will have been gone for so long. Lil will brim with sadness and rage for weeks. She will cry. William will cry. Hester will be puzzled and then she will not. My mother will be eaten up with anxiousness, and then her baby will come and she will have enough to do without worrying after me. I do not know about my father. Unburdened partly by my absence, he may say to my mother, “She is a big girl, Mary,” as he takes up his coppice tools for his walk to the Weald to find work again, or as he clenches his large, toughened hand around the handle of his flagon at table. Or he may not. A girl can never know a father.

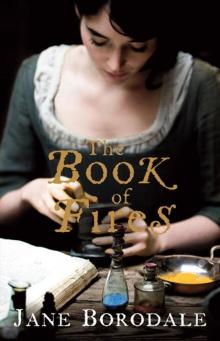

The Book of Fires

The Book of Fires